Coronavirus is changing the world in unprecedented ways. Subscribe here for a daily briefing on how this global crisis is affecting cities, technology, approaches to climate change, and the lives of vulnerable people.

By Matthew Lavietes and Enrique Anarte

NEW YORK/BERLIN, April 4 (Openly) - Andreas, a gay man living in Berlin, wants to donate blood but he is not allowed.

Germany's rules require that gay or bisexual men abstain from sex for at least 12 months before donating due to concerns over exposure to HIV.

But given the pressures on the blood supplies as coronavirus lockdowns prevent new donors coming forward, Andreas, who did not want to give his surname, has a solution - lie.

Coronavirus: our latest stories

"I have never lied to donate blood, but in an emergency, when the only thing keeping me from doing this is me being part of a risk group that is not warranted by my behavior, I feel it would be more responsible to lie and give blood," he said.

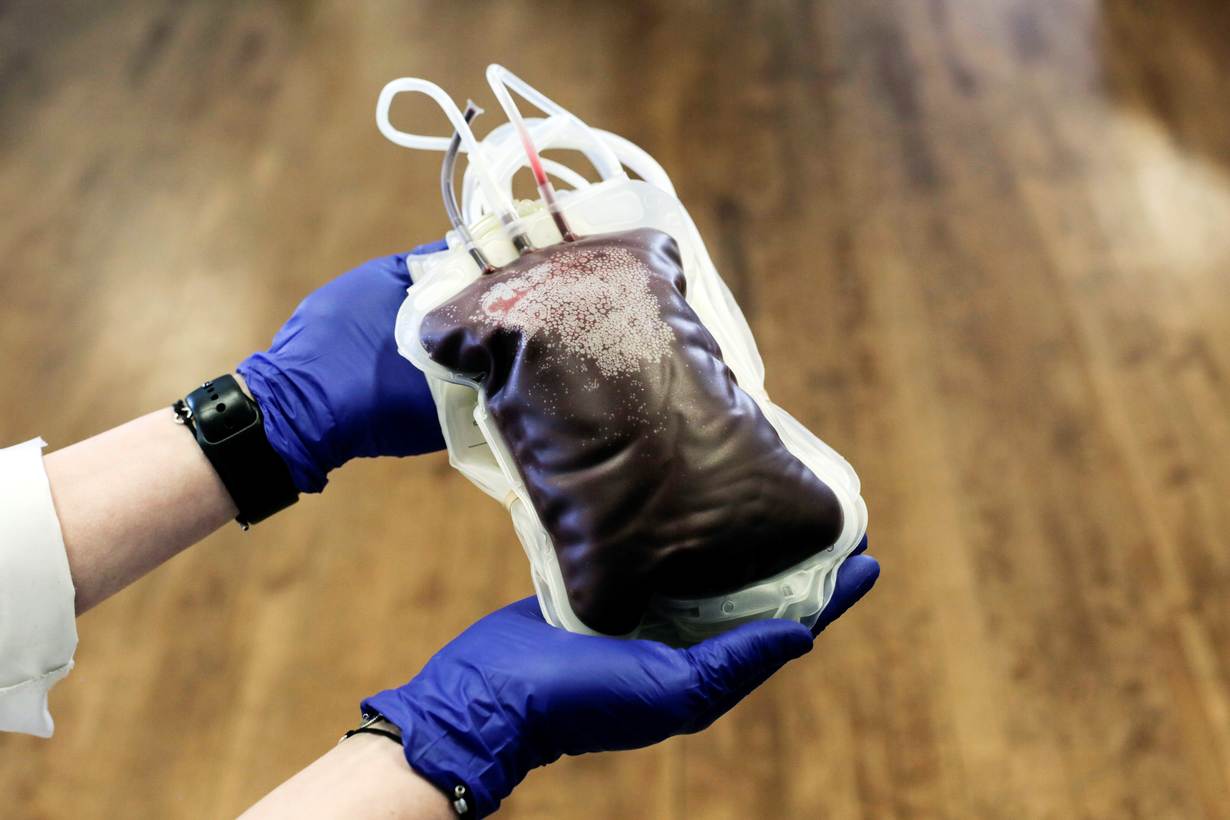

Blood supplies around the world are facing unprecedented pressures due to the coronavirus crisis with mounting calls to ease restrictions on men who have sex who men from giving blood, a policy LGBT+ campaigners have long decried as discriminatory.

Last week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cut a 12-month waiting period for gay and bisexual men giving blood to three months, having reported a dramatic slump in donations due to social distancing and the cancellation of blood drives.

Many countries introduced blood donation controls in the wake of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s when infected blood, donated by drug users and prisoners, contaminated supplies.

But Prof. Lawrence Gostin, director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center on National and Global Health Law, said science had since moved on.

"We've got a lot of categorical rules and with modern science, we ought to be able to do better screening," he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

INFECTED BLOOD

Globally the rules vary but as the spread of coronavirus increases and the available number of potential donors falls, many believe these waiting periods should be scrapped and brought into line with the policies covering straight people.

Britain and Canada require gay and bisexual men to abstain from sex for three months before donating.

Germany and Austria have 12-month deferral periods, while the waiting period in Taiwan is five years.

Singapore and Greece are among the countries that ban men who have same-sex sexual relations from donating blood outright.

The United States initially imposed a total ban on gay and bisexual men donating blood in 1985 at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic but eased the rules in 2015 to a 12-month wait.

"If you're being tested regularly and you lead a lifestyle that does not put recipients at risk, then you should be able to give blood," said Patrick, a 32-year-old translator living in Berlin, who did not wish to give his surname.

"Unfortunately, we live in a society where outdated ideas prevail."

LGBT+ advocacy group GLAAD welcomed the FDA's decision to reduce the wait period, but said it will continue to push for all bans to be dropped as this stigmatized the LGBT+ community.

"We will keep fighting until the deferral period is lifted and gay and bi men, and all LGBTQ people, are treated equal to others," GLAAD President Sarah Kate Ellis said in a statement.

German's Federal Ministry of Health declined to comment, but officials in Austria said coronavirus concerns would not influence official policy on donations from gay or bisexual men.

"The quality assurance of blood and blood products must always be a priority," a spokesperson at the Austrian Federal Health Ministry told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

HIV rates among gay and bisexual men in western countries have declined following widespread testing and the advent of PrEP, a daily pill that prevents the transmission of the virus by as much as 99%.

In Britain, new HIV diagnoses fell by 71% between 2012 and 2018, according to figures released by Public Health England.

"The MSM issue is a small risk that we can define better than we do at the moment," said Richard Benjamin, a former chief medical officer at the American Red Cross and now chief medical officer at Cerus Corporation, a biomedical products company.

"The system is not fair and equitable. There is a perception of discrimination and that leads to people not following the rules."

For Dr. Jack Turban, a resident physician in psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, who contracted coronavirus and recovered, the answer is simple - parity between straight and gay men when it comes to giving blood.

"Every time there's a crisis (and a) shortage, gay and bisexual men want to help," Turban said.

"(But) we just have to watch while this discriminatory policy perpetuates the blood shortages."

(Reporting by Matthew Lavietes @mattlavietes in New York and Enrique Anarte @enriqueanarte in Germany with additional reporting by Beh Lih Yi in Malaysia; Editing by Belinda Goldsmith and Hugo Greenhalgh Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Openly is an initiative of the Thomson Reuters Foundation dedicated to impartial coverage of LGBT+ issues from around the world.

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.